I’ve written previously about what book size tells us when dealing with education texts. Lately, I’ve had another beef with education books – also probably not a novel one, but one that needs to be shared nonetheless. Obviously the geeky bibliophile in me will lead the way through this post … you’ve been warned.

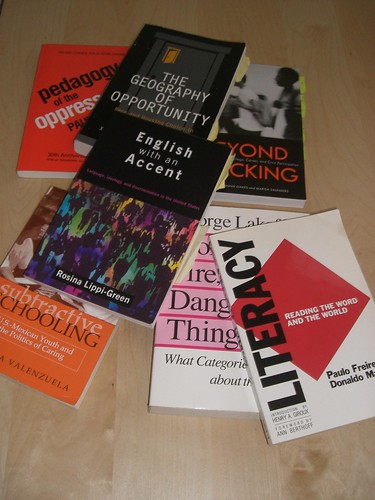

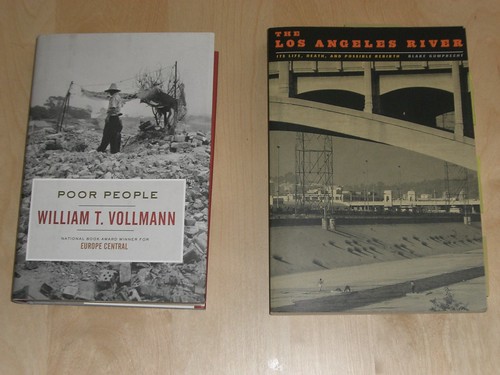

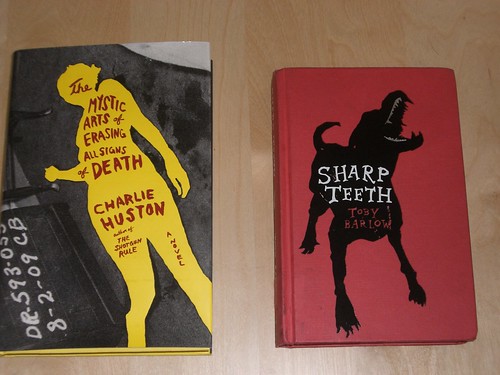

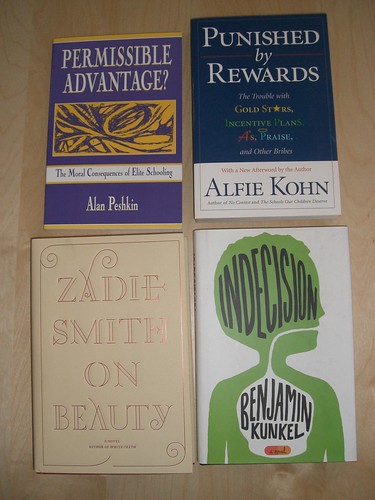

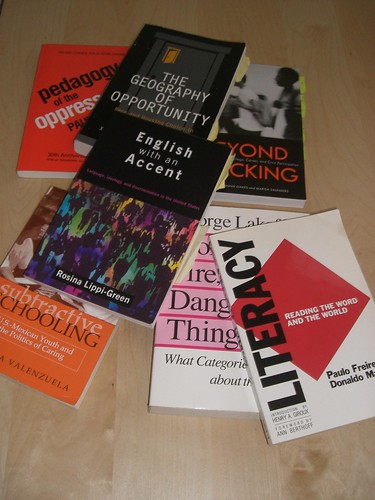

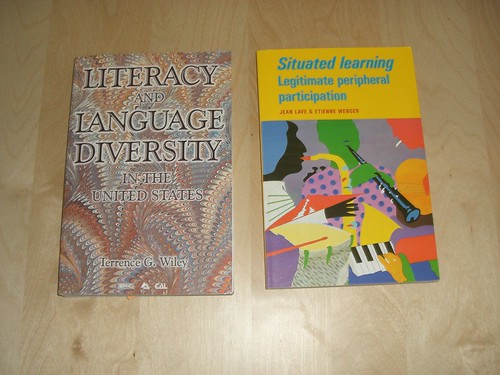

Look at all of these books:

These are all books that have some pretty important, exciting content in them.

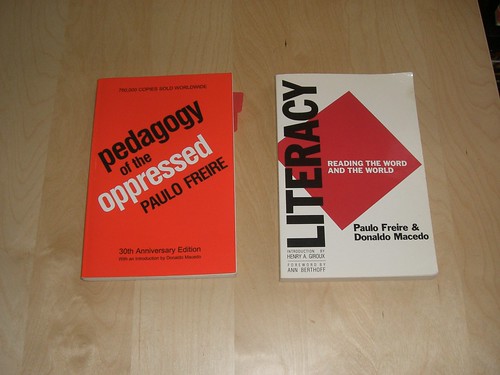

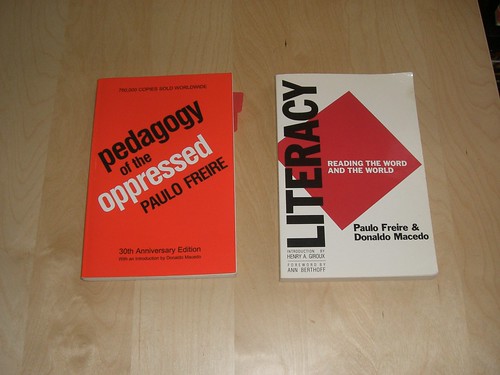

These two in particular have been fundamental in my growth as an educator (I’m sure I’m not alone in this feeling):

However, why, as educators, do we need to settle for texts that – despite the amazing content held within – are designed terribly? Just because a book is “academic” in nature doesn’t mean it has to be an eyesore, right?

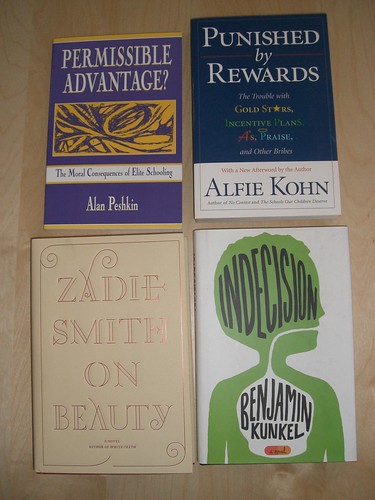

I mean these two books hurt my eyes just to look at them:

I realize that good design isn’t free and so the reliance on generic, quickly designed covers helps keep costs low. (Yeah right, like any of these texts are by any means “cheap”!)

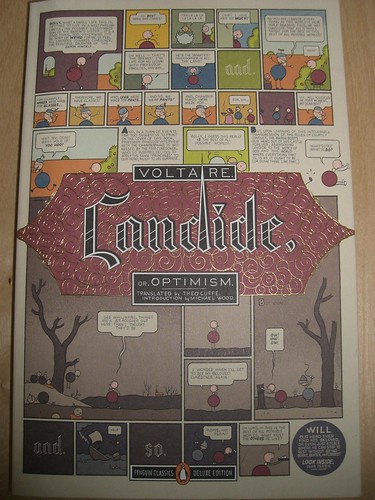

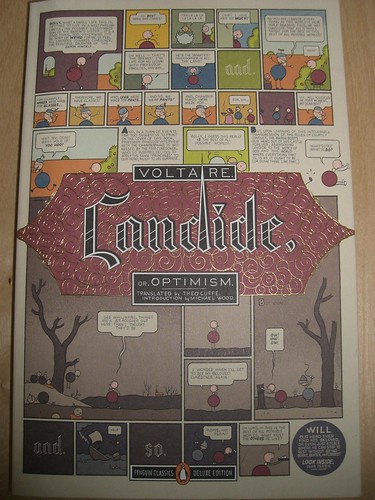

I’m not asking for anything fancy. Not everyone necessarily wants Chris Ware to design their covers. But if you are, I’d start with Candide (this photo does not do this [moderately priced] paperback justice):

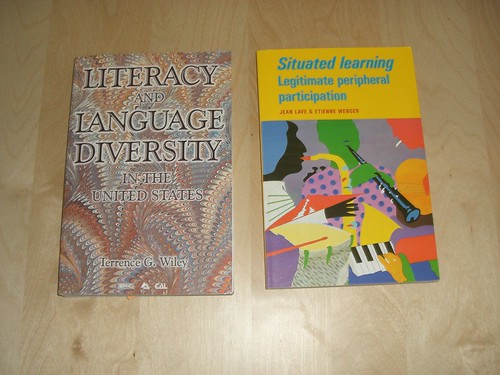

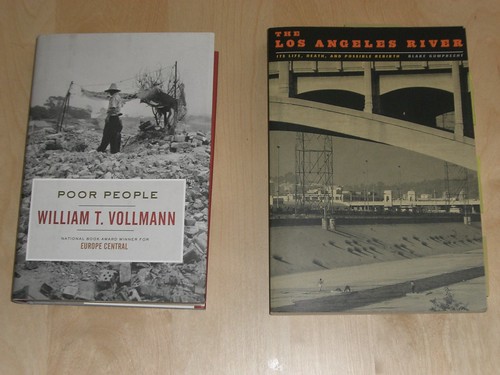

Book design doesn’t have to be fancy. A nice photograph and decently formatted text will make me happy:

Or even a decently designed graphic and text work:

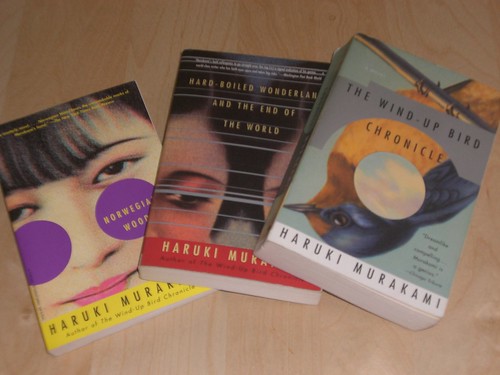

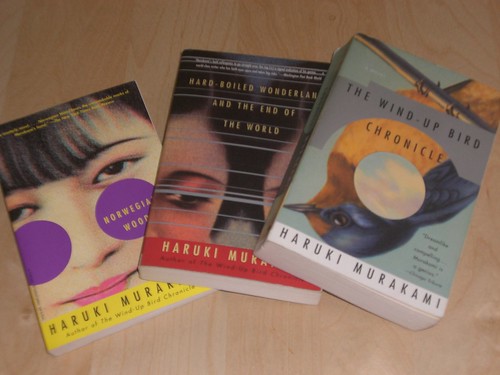

Likewise, if you’re creating a series of books, uniformity can make the texts shine. Here’re a few Murakami books that were sitting on my shelf:

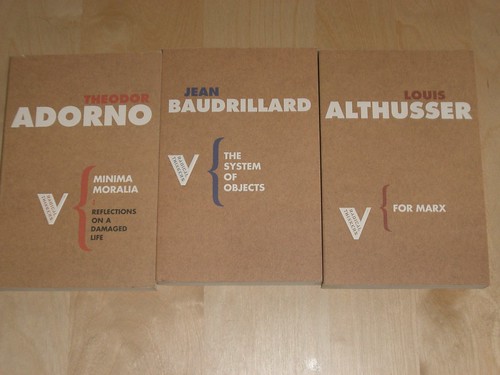

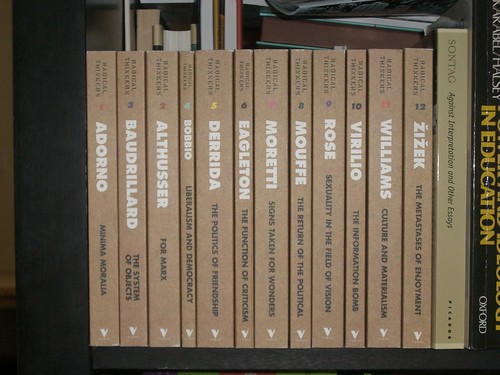

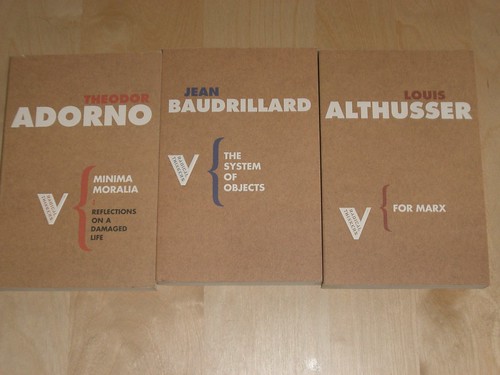

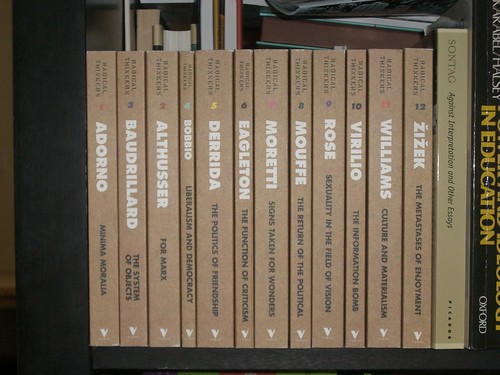

I appreciate the consistency across the texts. It’s easy for me to locate other texts by the author I may be interested in when I’m perusing a bookstore (remember those?). Simialrly, these minimally designed philosophy texts from Verso attest to the less-is-more aesthetic that even Ed. texts could aspire to and still feel “academic.”

And they look awesome on a bookshelf together (for the record, I’ve only read about half of these so far):

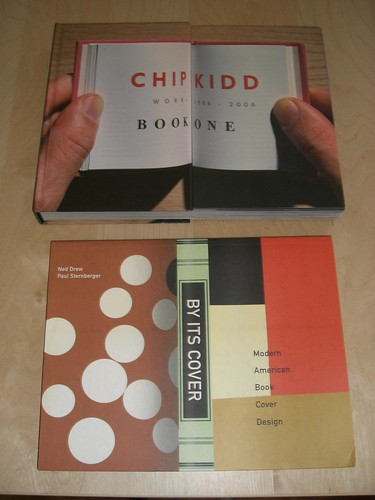

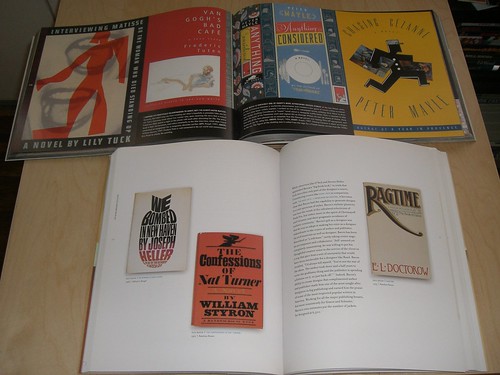

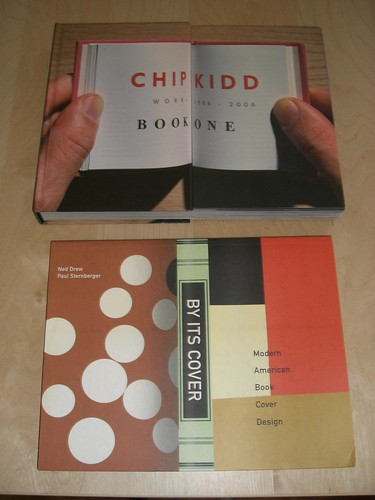

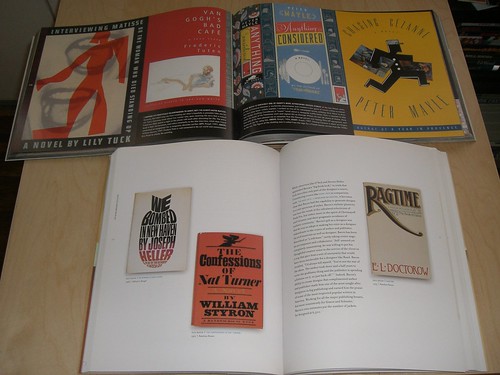

Chip Kidd is basically a book design legend at this point, so it feels odd not to mention him in this post. I guarantee you’ve been drawn to his book covers on countless occasions. A collection of his work as well as a book commemorating Penguin book design always feel inspiring:

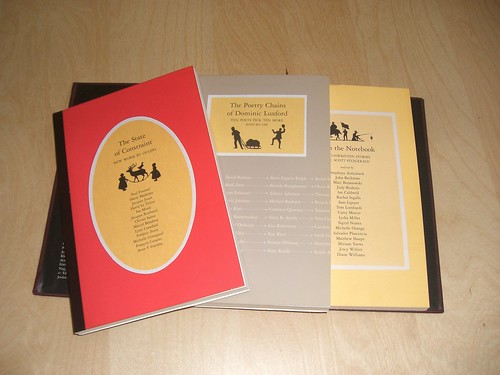

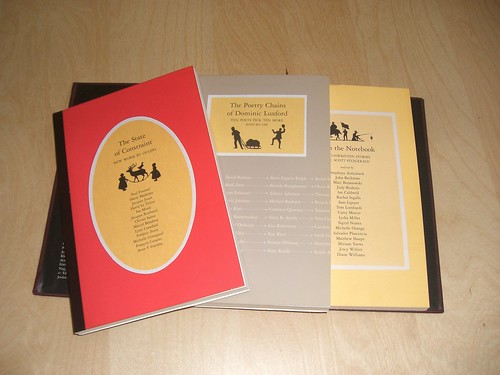

Similarly, I’ve been a fan of the design work being done through McSweeney’s for a while. Consistently, books and periodicals published by McSweeney’s are often beautiful, quirky, and “fun” for readers to interact with. This issue of their periodical was certainly one of the more “normal” issues: three separatly bound collections held within a larger, magnetic casing:

Ultimately, it’s not like most educators are going to stop reading or purchasing educational texts simply because of poor design. However, it feels like we should at least ask for better looking products. And who knows, maybe a non-educator might pick up the text because it looked interesting. Maybe one of my students will be intrigued enough by the beautifully designed book about education. Maybe that will be enough for a student to take a step toward a book that would otherwise look “boring.”

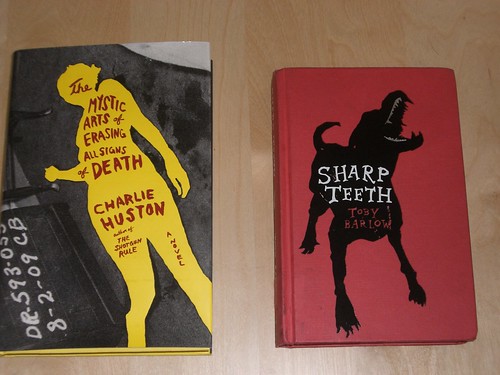

Even simple elegant design could be enough. Which two books here would your eye be most drawn to?

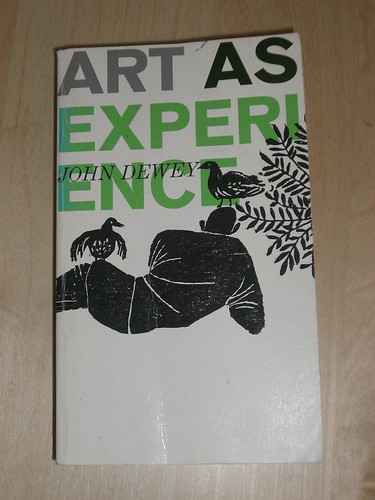

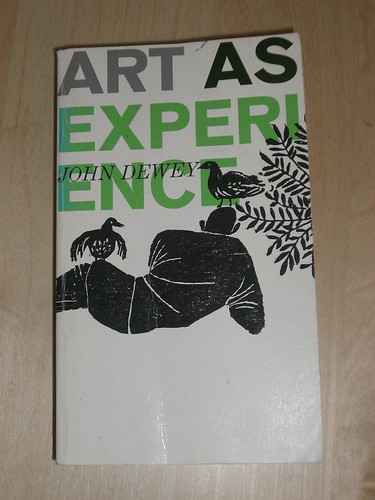

As a final thought, I want to point out the sole education-ish text who’s design I’m intrigued by. While delving into the typical education texts by Dewey, I stumbled across this gem, and the design alone compelled me to pick it up – it has since become a key foundation to my understanding of aesthetic, education, and self.

Tell people this is awesome: