Teaching ninth graders, the past month has been one centered around themes of conflict as my class analyzes Romeo and Juliet. Over this and a couple of future posts, I wanted to share some of the work my students and I have been engaging in. Essentially, the role of the seminal, ninth grade text, has shifted. No longer can students simply read and analyze Romeo and Juliet. Instead, it is not an option to include materials that exist outside of the original text; it is an imperative part of understanding the text. I’ll return to this idea after sharing some examples.

Utilizing the Flip Cams that Peter and I used for our What Son Productions course, the students will be recreating their own versions of scenes from the play. This is not an original or a very creative idea (more about that in a minute). What is interesting, though, is the process of reading Romeo and Juliet across different interpretations. As we read a scene, we may screen a scene from the 1996 Lurhmann interpretation as well as the 1968 Zeffirelli interpretation. We are then utilizing a 4×4 graphic organizer to note key differences between the original source, two films, and our own ideas of how the scene could be produced. These products are becoming the basis for a production log the students are creating as they note where one version may fall short – Tybalt being too aggressive to Romeo in the 1996 version before Mercutio becomes a “grave man,” for instance.

As I mentioned, the concept of asking students to recreate their own versions of scenes isn’t a very new one. In fact, as more and more students have easy access to tools of production – as these tools have become ubiquitous – it’s easy to see student work samples online. However, the vast, vast majority of these samples appear to be from overwhelmingly white communities. And these versions are taking significant liberties in their portrayal of urban reenactments of Romeo and Juliet.

Over the course of a week, I began each class by screening a 3-7 minute YouTube clip. I simply searched “Gangster Romeo and Juliet” and a deluge of student-created videos showed up showing “ghetto” versions of the play. [This was inspired by a conversation about developing this unit with my colleague Peter Carlson.]

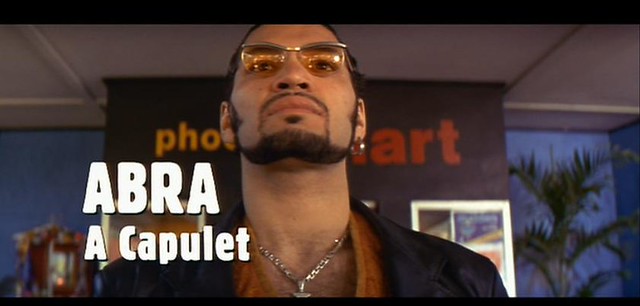

This ghetto, however, is technically the community my students live and go to school in. This ghetto is stereotyped by white students in ways that at first issued guffaws. My students found the videos funny at first. However, after a couple of days, students said they felt “mocked.” They said that the videos didn’t show things correctly, were making fun of the community, and actually lacked textual understanding of Shakespeare’s words (several of the films, for instance, abbreviated Abraham’s name the same way that Luhrmann’s did).

Often times, these videos are posing these ghetto versions in lush, rural or suburban communities:

I want to underscore that I am not using these examples to criticize the students that have made them. However, when discussing them with students, we have noticed that there are not similar “ghetto” versions made by people of color. And if they are not creating them, essentially, an incorrect truth about what the ghetto is and how people act within it is being reified. My students shifted uncomfortably in their seats as they began thinking about the messages that a critical mass of lighthearted “ghetto” student clips are sending; these paired with YouTube clips of student fights are furthering stereotypes of student behavior and expectations.

As educators, our role is changing; the power of student production is a necessary tool for critical analysis. How can these tools break down existing assumptions?

As a class, my students are thinking about how they can create videos that respond critically to the samples they’ve seen, accurately reflect a nuanced understanding of their neighborhoods & worldviews, and express thematic interpretation of the canonical text. It is the necessary hard work I am excited about seeing develop in the next two weeks.

Again, as I said in the opening paragraph, the role of Romeo and Juliet is much more inclusive than simply the 92 pages of the Dover edition that my students have each been asked to purchase. The culture and understanding of the text is inclusive of a rich body of knowledge, assumptions, and continuing dialogue with the work through writing, acting, and recording. Social networking, new media, and a changing access to technology means that simply summarizing plot and theme is disregarding the other critical skills students need to learn in an English class.