Could you maybe try to explain why the name is offensive but without saying “white privilege”? I think people stop reading when they see phrases like “white privilege” or “supremacy.”

So began one of the more surreal questions I’ve been asked by a reporter.

Just to be clear: I was being interviewed about the power of words to hurt, to condemn, to offend.

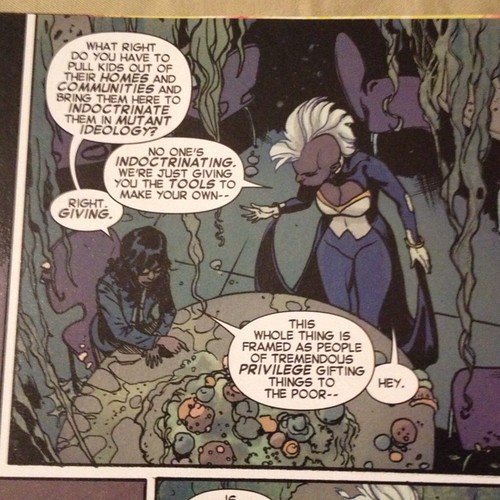

Particularly around an issue that focuses on the politics and violence of language, I’m struck by the fact that the vocabulary necessary for discussing societal context is, in itself, too confrontational for newspaper readers*.

I should state, here, that I’ve been conscious of speaking more to the role of “white privilege” in the discussions of the name Illegal Pete’s than of a culture of “white supremacy” because the later will sound more radical and offensive to readers. Though it is language I theorize and use in my college classes and writing–invoking the language of bell hooks–I realize that “white supremacy” sounds too confrontational in a newspaper; it shuts down dialogue rather than opens it up. In case you’re wondering, here’s hooks’s description:

To me an important breakthrough, I felt, in my work and that of others was the call to use the term white supremacy, over racism because racism in and of itself did not really allow for a discourse of colonization and decolonization, the recognition of the internalized racism within people of color and it was always in a sense keeping things at the level at which whiteness and white people remained at the center of the discussion. In my classroom I might say to students that you know that when we use the term white supremacy it doesn’t just evoke white people, it evokes a political world that we can all frame ourselves in relationship to.

My original letter to Pete (which subsequently ran in the local paper) described “white supremacy.” And, resultantly, was misinterpreted and denounced.

However, even the language of “privilege” seems too much for readers according to the reporter. As someone that’s been accused of being too “PC” throughout this ongoing dialogue, why are the words “white privilege” so offensive to readers?

While I do not have empirical data, I can imagine the general demographics of the folks that have emailed me and commented on my blog and articles. Inferring from names, I suspect they are largely white and male.

In her book Other People’s Children, Lisa Delpit discusses societal power and classroom life:

- Issues of power are enacted in classrooms

- There are codes of rules for participating in power

- The rules of the culture of power are a reflection of the rules of the culture of those who have power

- If you are not already a participant in the culture of power, being told explicitly those rules of the culture makes acquiring power easier.

- Those with power are frequently least aware of – or least willing to acknowledge – its existence. Those with less power are often most aware of its existence.

Pointing to power and privilege and difference (invoking another academic text), perhaps it is the highlighting of power that makes the words “white privilege” so anger-inducing. Being asked to see how privilege still exists in the 21st century and how it is tied to race is difficult to accept. Reading Talib Kweli’s problem with the “N-Word,” I am reminded here that “Context has consequences.”

—

I should note that, in a conversation with Ally, she pointed out that much of the arguments I’ve made about the name Illegal Pete’s are centered on the same issues my scholarship on young adult literature and pop culture also focuses. My thoughts on Wreck-It Ralph, on Kanye West, and on Gossip Girl, for example – all challenge how invisible the privilege we carry can be. In the words of George Clinton: It would be ludicrous to think that we are new to this/We do this/This is what we do.

—

* There is an unspoken irony here that pertains with the readership of my local newspaper. One aspect of the Illegal Pete’s issue that I struggle with is the fact that I only learned of the restaurant and its opening three weeks before it was to begin serving food in my community, despite the fact that it was covered by the local paper. Considering this was similarly the response of many of my co-organizers, one has to wonder if the paper is reflecting the voices, interests, and needs of its Latino community. Maybe this news wasn’t delivered to us in time because this newspaper really hasn’t cared about covering Latino issues (or covering them adequately as the shoddy coverage of the change the name meeting suggests).