The Speculative Education Colloquium took place last week. Across two days of breakouts, featured speakers, and engaged online dialogue we expected a couple dozen people to join us for this event. We had several hundred sign up instead. In terms of our original hope of furthering a space for imagining critical pathways forward in education and educational research, the event feels like a successful one, though there are some areas we learned from that I think we can share with others here.

While the substance of the convening will hopefully yield breakout groups, offshoot gatherings, and classroom practices that may funnel into the public in the future, I wanted to reflect on the process of putting this event together and some of the lessons that Nicole and I learned. We announced the event three weeks before it took place and–including selecting dates, format, and inviting speakers–the entire project was a month long from start to finish. This design post-mortem is intended to help others plan for similarly-scaled events utilizing online virtual platforms.

Make it Happen

The biggest piece of advice that I think we can convey is that–if you are at all interested in bringing folks together, to sustain community and to engage in collective dreaming–do it. There are a lot of us sitting in physical distance from one another who are ready for something (virtually) tangible for us to work toward or learn from. To be honest, my own scholarship has suffered over the past two months. Stringing together academic writing, engaging in sustained data analysis, doing the hard work of substantial paper revisions: these are things that, cognitively and emotionally, I am having a hard time attending to right now. I imagine that’s the case for a lot of us. However, bursts of energy (ahem, maybe blog post-length): I can do that. And so, whether it’s hosting gatherings, writing shorter, accessible essays, or reviewing academic manuscripts, things that take discrete sets of time to complete are at least conveying the feeling of productivity (for myself) during a time when it’s okay for us to not actually be productive; this labor/market tension–particularly in the academy right now is a slippery one–I’ll probably ramble about this elsewhere. The convergence of this anxious energy with the willingness and creativity of an academic collaborator I’ve been lucky enough to learn alongside meant making space to create this event feel rejuvenating and personally useful. If any of this resonates with you and having a community to engage around your thing would be useful, do it. While somewhat labor intensive, this was a fun event that I feel nourished by. You can do this too.

Lower the Stakes and Under Promise

As mentioned above, Nicole and I (really) expected a handful of people to join us. We expected this to be a low-stakes event for sustained conversation for a couple days. For us, we had time open on our calendar because AERA was cancelled and–worst case scenario–the two of us would use the time to talk about a topic we were interested in. Even if no one else came, this event’s space and time would have been useful for us: it was a no-lose situation.

Once we sent out a general invitation to speakers and to the general public, we didn’t make any grand promises: come gather for a bit and we’ll see what happens. It’s free and so if you don’t like it or you can’t make it anymore, no harm done. We did ask participants what they were interested in (and saw a wide range of responses). That feedback shaped our breakout rooms and hopefully led to smaller, independent activities that could emerge from the event’s collaborative document.

Be Flexible

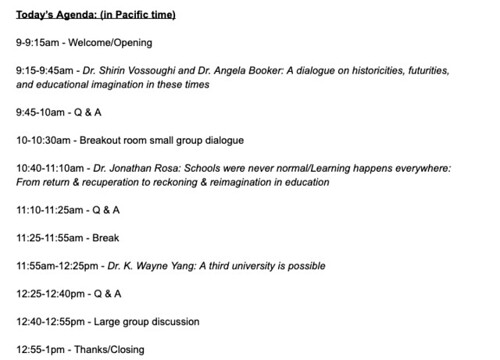

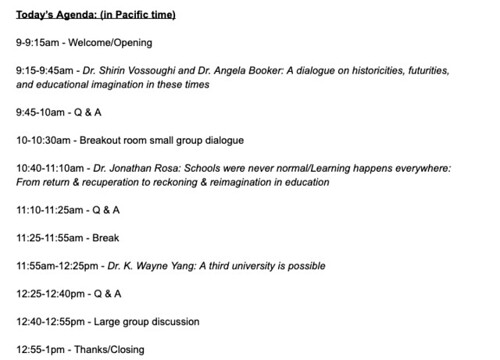

Once 100 people signed up for the event–two days after it was announced–we figured about half of those people would show up and the event was now larger than what we originally envisioned. We were in a tricky situation: we were too big for a collective dialogue (or at least we thought we were) and we were lucky enough to have all of our speakers confirm that they would participate. This made our schedule tighter than we expected–instead of having a few dozen people in close conversation with Megan Bang, for example, we could all listen to her, have limited time for Q&A, and have two breakout sessions. This wasn’t what we planned, but we went with it. If you are doing an event like this, consider how you might scale the context to accommodate larger and smaller groups. Further, how can you do this scaling in the moment? For example, we had a large number of breakout rooms prepared to be facilitated by friends; if we had much fewer attendees, we would just cancel a few of these rooms to make the others create fuller spaces (this didn’t quite work out and I’ll talk about that below).

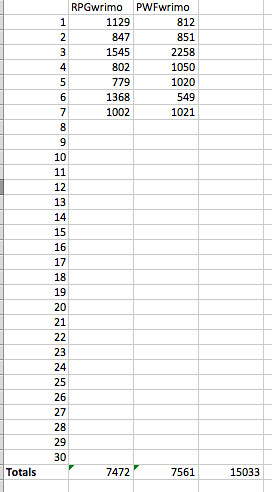

A quick note on sign ups: before the event started just over 400 people signed up. We circulated this invitation only via tweets and Facebook posts and hoped it reached people who were interested via word of mouth. Of the people signed up, we had a peak of 220 (or so) people during the colloquium and the number dipped as it got closer to each day’s conclusion. We expected about half of the people signed up to join and that seems like a decent rule of thumb for online, free events in general.

Find Synergies

We knew most of our speakers would likely have attended AERA and so the ask for their participation was an easier one. This event intentionally moved alongside similar scholarly interests–our framing for the event was based on the invitation by Drs. Na’ilah Nasir and Megan Bang and clearly aligned with the scholarship of each of our speakers. Though these speakers were clearly making innovative leaps in the new work they presented, the request to share within the context of this colloquium wasn’t exactly out of left field. I do want to note that, as a free event that was not affiliated with either of our institutions, we did not have funding to compensate the donated labor and energy of our six speakers. That is something I think we would try to address differently in the future, if we were to do one of these events again.

Be Vigilant

The things that Nicole and I were most worried about were chat spamming, zoom-bombing, and other forms of online harassment that might have occurred. Two days before the event, the AERA online Presidential Presentation had to turn off chat functionality during Dr. Vanessa Siddle Walker’s powerful address because of comments made in the chat. Particularly considering that all of our speakers were presenting from and addressing scholarly and personal commitments to historically marginalized communities, making sure that online harassment did not occur was our fundamental concern and point of stress for the event. We know that the forms of harassment that we are concerned about disproportionately affect BIPOC, women, and members of the LGBTQ+ community.

To our knowledge, we did not have any issues with trolling or harassment during the event. While we cannot account for private messages that may have been exchanged or communication after the event, I feel proud of the work we did trying to ensure this space was a safe one.

We spent substantial time prior to the event testing out and confirming security functionality for the Zoom. We only sent links to the password-protected Zoom the night before the event, to minimize interlopers. We had a waiting room and let people into the event by first trying to confirm their names based on our sign up. We had multiple co-hosts of the Zoom and we were all in communication on a Slack channel identifying potential usernames we did not recognize or comments that raised any flags for us. We all had practiced the processes for turning off chat, ensuring participants could not share their screens, and–if need be–kicking people out of the event. When speakers were presenting, we also disabled participants’ ability to unmute themselves, ensuring the speakers would not be interrupted. These sound draconian, but we would rather a vigilant enforcement of safety than an unsafe space for our participants and speakers.

Most importantly, we wrote–and announced each day–a code of conduct for the colloquium. This was substantially adapted from a policy written by the Assembly on Literature for Adolescents of the NCTE.

While I don’t love the need for such rigorous moderating of the event or the fact that so much of this insecurity is based on our over reliance on proprietary software that governs so much of our online interactions, it was the choice we made. We could have spent substantial time at the beginning of the event establishing collective norms with our participants–if we were a smaller group we probably would have. However, given that we wanted to prioritize the content of this colloquium, we went with the decisions noted above. I would be curious what strategies others are employing right now.

Ask for Patience

There are a lot of ways this event could go wrong. At the beginning of both days and in our email communication with participants, we asked everyone for patience as we collectively figured this out. Maybe it helped (?) that the first email I sent out about this was unintentionally formatted wonkily, immediately lowering people’s expectations (fortunately, Nicole took over emailing participants for the event moving forward!). Again, because this event was free, if things didn’t quite work out–like when the Zoom meeting abruptly ended for everyone at the end of Day 1–we could all smile and let the learning and convening continue.

Some Pain Points

There are a few areas we know we could have improved in this event and I share these below.

Access

We could have been better when it came to accessibility for this event. Yes, that’s the case broadly in schooling and particularly for forms of distance learning right now, but for our event, this could have been better. Three weeks prior to the event we started looking into captioning options. We made weekly progress getting the right APIs to talk with one another to enable automated captioning; while we didn’t have funding to hire someone to type captions for the event, we were planning to pay for the cheaper and still less ideal automated captions. Up to 24 hours before the event took place, we expected this to be functional. However, with various security levels to fiddle with Zoom, we were not able to get this option set up in time. We are aware that this likely affected some participants’ engagement. To be clear, this isn’t the only form of accessibility we needed to consider and this event had shortcomings among multiple lines in this regard. Early on, we acknowledged that a virtual convening like this one privileged folks with access to strong internet connections, for example.

Recording

This is less a pain point for us than for people who want the content from speakers. Even before the event was concluded, we were getting requests to share the videos of the speakers from the colloquium. Honestly, every speaker was amazing. And while we will share some of these talks very soon, we also were explicit with our underpromise in this regard. We only recorded the speakers’ presentations, cut off the recording once public Q&A began, and conveyed to everyone that we were uncertain if these recordings would be made available publicly. Again, our intention wasn’t to amass and collect others’ knowledge. After the colloquium, we emailed each speaker a link to download their own video recording. It is their work and their file to decide what to do with. We wanted to shift responsibility around this work to give back to speakers–particularly scholars that data suggests are often less cited or recognized for their contributions–to ensure that knowledge is both preserved and moved forward in ways that are responsive to individuals. Depending on your event, we could imagine you choose to record or not record in different ways, but think intentionally about what that recording light on Zoom calls does for participation. Speaking of …

Participation

We collected comments and questions from the chat, asked participants to “raise their hands” through Zoom’s functionality, and had a robust hashtag on Twitter as inputs for participation. There was also a powerful social annotation effort happening alongside the event. However, the size of the event meant that these structures did not ensure that everyone’s voices were heard. It also meant that it sometimes felt like there was a disconnect or lack of engagement from the large group if questions didn’t flow for speakers at some points. It also didn’t help that Stanford’s Zoom settings disable copying text or clicking on links.

Some strategies we used to mitigate these limitations—that might be helpful for you—included abundant use of customized tinyurls and an open google doc. The tinyurls were easy to share on a screen and, even when participants couldn’t click them, weren’t too difficult to type into a browser. In general, all of our information was distilled to a single, read-only google doc that we updated frequently. On this doc, we would post the agenda, links to all breakouts, links to related information, and things like a concluding evaluation form and the aforementioned google doc. In essence, if participants could access this document they could get to any other materials for the convening pretty easily.

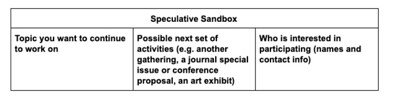

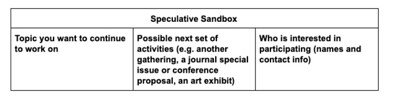

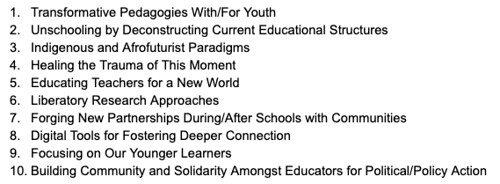

The open google doc functioned as a sign-in page so that participants could share contact information, converge around interests, and offer any relevant resources. There was a “sandbox” that we encouraged individuals to use to cluster around projects and topics–revisiting it now, there are several pages of potential projects that were born out of this event. This was an unorganized space and—again setting lowered expectations—we were not building a listserv or database to share later. Rather, we hoped people would use this space in the moment. At the beginning of the first day, we hit the limit of how many participants could be on this doc at any given time, so this may not be a feasible space for events of this size or larger.

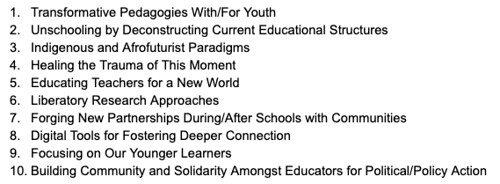

Breakouts

Our breakouts were named based thematically on the interests people listed when they signed up for the colloquium. Participation in them varied widely. Some breakouts had 30-50 people in them and some had 2 people in them (though facilitators noted that these smaller groups had robust and personal conversation as a result). Because we didn’t want to sort people manually into groups or to assign people to random rooms, we solicited the help of friends that we knew signed up for the event. Since most of us have institutional Zoom accounts, Nicole organized rooms using multiple folks’ accounts:

Again, the read-only google doc served as the hub for finding these sessions. In addition to a host for each room that served as the space’s facilitator, Nicole also created a note-taking generic document. This page was shared with breakout rooms individually. All of these spaces, links, and organization took time in advance to make the day of the event flow somewhat seamlessly.

Returning back to the main meeting space from Zoom—like reconvening from group activities in a class or like a broader conference session—took time and we should have given ourselves more of it for this. We also saw some drop-off of attendees (who likely chose not to participate in the smaller breakouts); this didn’t surprise us, but I note it here for your own planning considerations.

Competing Activities

The same week that we announced this colloquium, Nicole and I also shared an adjacent (but different) idea, called #RogueAERA. Our attention to this colloquium meant we didn’t spend as much time on #RogueAERA, though there were some amazing contributions to the hashtag. However, because we had two different (but kinda related) hashtags floating around at the same time, we saw a lot of overlap between the uses of these spaces. Both #SpeculativeEd and #RogueAERA served as back-channeling spaces for the event, even if that wasn’t our intended outcome. I note this here to consider how you might make clear the boundaries of your space and the need to be flexible when participation begins to seep beyond those boundaries.

What’s Next

We aren’t sure! There are so many different things that could emerge from this colloquium. None of them have to be organized by Nicole or by me. This is an open invitation for others to lead the what’s next. I know this event is helping shape some of my own thinking and it is helping me ease back into the scholarly writing I had been adrift from.

Finally, about three weeks prior to the event, we did receive–via the Center to Support Excellence in Teaching–the support of Stanford doctoral student Kelly Boles; she played a substantial role organizing and working on the logistics with us. We really appreciate getting to learn with Kelly on this project. Alongside her, we are also grateful for the support of friends and colleagues that hosted breakout rooms, Joe Dillon and Remi Kalir’s work facilitating the social annotation for this project, and the many participants that tweeted or contributed resources throughout the event.

Tell people this is awesome: