Last month an article I co-authored was published in Learning Landscapes. “Transforming Teaching and Learning Through Critical Media Literacy Pedagogy” can be freely read and downloaded here.

And now I want to talk a bit about copyright and fair use and critical media literacy.

In writing this article with my colleagues, Robyn and Jeff, one of our central arguments is that Critical Media Literacy today is fundamentally pushing toward a more productive space. Tools now standard on computers, easily installed on mobile devices, or quickly googled on the ‘nets make making really easy. As a result, critical media literacy in classrooms today has to shift even more toward critical production instead of just criticism of mass media products.

This is something Jeff and I (along with a few of colleagues – Peter Carlson, Mark Gomez, Clifford Lee) tried to do in a set of graduate classes for preservice teachers in Los Angeles. The students in these classes were constantly creating media products. Some of these projects are described throughout our article.

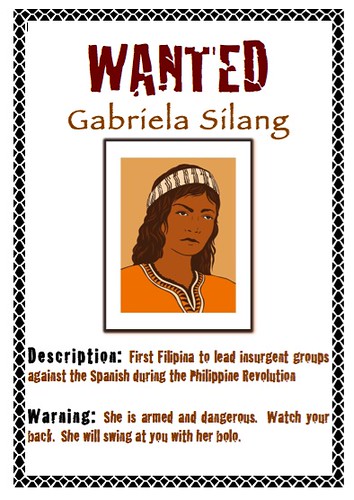

In our original manuscript several images were included with the descriptions of how these student-created products extended a pedagogy of critical media literacy in the second decade of the 21st century. Most of these images are featured in this blog post. While making revisions to our manuscript we were notified that our images may be a conflict with regards to copyright and we were asked to take them out.

Before I go on, I should be clear that I am not an expert when it comes to copyright law today. It is a passing interest: scholarship by Lawrence Lessig and Aufderheide and Jaszi (in particular their 2011 book Reclaiming Fair Use) inform much of my practice and the workshops I’ve run (such as a one for the UCLA Writing Project called “Copy Left, Right, and Center”).

In discussions with teachers I emphasize four main components of fair use:

- Purpose

- The nature of what is being used

- The amount

- The effect

Note that those four components of fair use need to be taken collectively. This isn’t something teachers always consider and, I suspect, many of us infringe on this in ways that highlight how archaic these laws are (and if you’re looking for someone to blame, I would read the slightly dated The Pirate and the Mouse or watch the doc RIP: A Remix Manifesto – though this one slightly conflates different copyright laws).

Let’s unpack an example: say you are asking students to create a video slideshow about a book as an assignment and say that a student chooses to have an appropriately thematic song playing in the background. Maybe this song is a chart-topping pop song. This seems like a typical assignment students would engage in and a creative (and easy) way for kids to customize their interpretation of the work. However, this would not be considered fair use: the song is not used in a short enough amount (though there is no specific time length in legal documents despite what you may have been told otherwise) and the song’s purpose and effect are not significantly different from what they were in a non-school context. I should also point out that being a teacher or using media in a classroom does not grant us special exception from copyright law. We just usually infringe unknowingly.

While all of these components of fair use are not simple to quantify, they act – as Aufderheide and Jaszi note – as the spectrums across which legal actions are determined. Because the images we included with our manuscript (and featured here) are not of commercial quality (they could not be used professionally in the dpi we have submitted) and because they were to be used in ways that clearly and intentionally change the original meaning, they seem like an appropriate case of fair use.

In the fair use research I’ve done, the importance of using others’ work in transformative ways is underscored. I think this is a key point of the critical media literacy article and of the images we were using.

I should also add that I don’t think copyright laws really help media producers innovate today (which, as Lessig argues, was the whole point of copyright to begin with). I don’t describe how I–along with lots of other teachers–probably unknowingly infringed on these laws as a teacher because I think they are good laws. I’m stating my understanding to help somewhat clarify the linearity of my thinking with regards to this article.

Ultimately, my appeal that these images constituted fair use was not enough for the editors to feel comfortable including them. I should note that I do not fault the editors and appreciated their consideration and dialogue throughout the process. The images highlight the challenges of how participatory culture confronts the dilemma of traditionally consumer-driven media markets. Fair use, copyright, and advances like creative commons are areas of this research we did not address in our article and that we need to continue scholarship around in the future.