I was sitting on the deck of a pirate ship in a non-descript office building in San Francisco celebrating the nuptials of my close friends from earlier in the day when a voice next to me said, “I heard you like Kanye West.”

I knew it was bait. And I took it.

An hour later and my voice is straining above the usual din of pirate ship-themed bars in non-descript buildings and I’m on my second tropical drink and haven’t even really gotten past the most recent album and the whole “leather jogging pants” thing.

A week later my friend Cliff posts this article about Kanye West, Frantz Fanon & Double Consciousness by Jessica Ann Mitchell. I shared the article on my own Facebook page with the amendment, “I am preparing a Kanye-like rant on why Kanye is the most important cultural figure…. ever (Kanye was not above hyperbole).”

And so, agreeing with one of my good friend’s brother, I want to tell you why “Everyone should want to be like Kanye.”

On Not Burying the Lede

There are two things I learned back when I was doing a lot more music journalism that are appropriate for this post:

- Don’t bury the lede. As rant-heavy as this post will be, here’s what you need to know: the very things that make Kanye reviled today are exactly what we need more of. In particular, I want to focus here on why we need more men of color being indignant and not settling for labels like “brash,” “petulant,” or “pompous.” I am not being ironic when I say that Kanye’s actions are revolutionary in intent and execution. And while I agree with the thesis of Jessica Ann Mitchell’s article, I also believe that Kanye’s confrontational behavior is not simply Dubois-like “double consciousness” but as distanced a move as Kanye can make within the capitalist mechanisms his profession has entrenched him in.

- The second thing I learned as a writer was to not pull the hipser-y card and describe music by just name dropping other artists. For example, for Yeezus I wouldn’t want to say, “Imagine Metal Machine Music for the millennial hip-hop generation.” You’ll see this move from music journalists a lot and it’s a lazy one. Name dropping and using the “it sounds like” are a big no-no: “yeah man, imagine if Rick Rubin produced Johnny Cash’s Folsom Prison live album and told him to only cover Hall and Oates songs but in the style of Philip Glass.” [Aside: but seriously, imagine how awesome that album would be.] While it would be convenient to throw in a litany of other artists and activists that help define Kanye’s actions I want to follow in the footsteps of his ego and focus on Kanye. As an individual in America. Today.

- (Okay I said only two things but …) I’ve written at length on this blog about how we can extend critical pedagogy vis-à-vis Kanye’s work. I would encourage educators to look here for less rant-y thoughts with clearer theoretical and pedagogical ramifications.

Since this post spilled beyond the 2k word count, the rest is below the jump.

More Preamble: I’m Getting Old

I want to start by acknowledging the fact that I’m getting old. I don’t know what the kids are listening to today. My TA taught me how to use Snapchat earlier this week (to talk about books like Gossip Girl and TTYL no less). I regularly hear the names of bands that sound foreign to me. And so when I discuss Kanye below it isn’t under the assumption that he is the apotheosis of “cool” for today’s youth culture; I think he’s actively pushing against being for the cool kids at this point.

I’ll also offer the amendment that I don’t “get” a lot of high fashion. That whole leather jogging pants thing? No clue. [As an aside–there will be a hefty amount of asides throughout this, it’s Kanye-like–I did just watch an incredible documentary on photographer Bill Cunningham and love how he is able to weave this narrative between the lives and clothes of “real” women and the work on runways and the history of high-fashion over decades.]

That being said, the glory of Kanye West, for me, comes full circle to a moment long before his first album was even released.

A Stereotype in the Making

Let’s revisit that time in the early ‘00s when it didn’t get bigger than the Black Album and Clipse were still making the kind of minimalist trap beats that make me feel nostalgic when listening to the Lorde album that’s currently playing on my laptop. [Aside: I totally missed the Lorde thing when the whole discussion of racial politics was coming about. I heard the song (you know, that song) on the radio and told Ally how catchy I thought it was only to receive an exasperated eye roll that it had already been played out. Like I said, I’m old now.]

And this is still the Kanye we think we know as an artist. This is the sped up soul-sample Kanye that changed things up by going back to hip-hop’s roots. From samples for Jay Z to the inescapable “Through the Wire” the Kanye that was an opening act for Dave Chappelle’s Block Party is the listener-friendly, funnily cocky Kanye. His swagger fit the trope of the confident black man and that was great. And much of white America even gave him a pass for his 2005 “George Bush Doesn’t Care About White People” stunner. He spoke truth to power and this is where America supported Kanye. [Aside: I wanted to point folks to the history of the phrase “speak truth to power” and Wikipedia wasn’t coming to the rescue. I started a Wikipedia page for the entry here. A sentence and a citation. Let’s grow this.] In 2005 we loved Kanye because he was a young black man shooting from the hip for what he believed in. This was confrontation and we liked it.

It was the stuff he did that was confrontational after this that shifted our attitudes. I won’t run down the list – it grows regularly and currently includes selling merchandise on his tour that features a confederate flag. We can recognize the lasting effect of Kanye’s “Imma let you finish” speech. His bullish behavior and the timid look of Ms. Swift shifted the narrative we had of Kanye: now he is seen as reinforcing the image of the primitive and dangerous black man.

We can recall where Kanye goes from here: there is more of Kanye firing on all cylinders, creating music that toasts “douchebags” and “assholes” and essentially embracing the cagey labels that have been placed on him. We could weave a narrative here that he is appropriating the same language that castigates in the same way “Queer” and the “N-Word” have been re-appropriated in recent years. But one man is not a movement and I want to pause this pathway for a moment and return us back to Clipse and the Black Album.

Going Back Home

Don’t you know that things go in cycles? – Tribe Called Quest

This is years ago –a decade now–months before College Dropout dropped. [Aside: why are regular albums “released” but rap albums get “dropped”? I imagine this is related to dropping the needle on new vinyl, but the metaphor has been moved and the d-word has become the urban signifier for writers today.] I downloaded a supposed Kanye West album: my interest picqued by his innovative samples and “Through the Wire.” It was someone’s pruned collection of Kanye songs floating about the ‘nets. It began with that Def Poetry Jam video above [Aside: Check out Kanye’s canon-shattering introduction into the world, describing his intent of being “the best dressed rapper.” Here is Kanye, no album to his name, already trying to confront the hip-hop figured world].

But that piece wasn’t the most interesting track. Instead, it was the song “Home.” Take a listen:

What are the connections we hear? Well, it features the same lyrics as his song “Homecoming,” which would be released five years later and replace John Legend with Coldplay’s Chris Martin (a move to build pathos with and speak to a whiter listening audience, perhaps). It is also a part of a tradition of hip-hop songs that function as odes to rap music, even quoting directly from the most iconic of these song’s Common’s “I Used to Love H.E.R.” But it’s not John legend that makes this song so great or even the way it’s like Common’s song. It’s the relentless, sampled loop. It’s Patti Labelle & The Bluebelles’s “You’ll Never Walk Alone.” In Kanye’s hands it becomes a relentless, heartbreaking, and overbearing expression. [Aside: but expression of what? I think this is still Kanye learning to wield these samples in ways that become more purposeful later in his career.] I said I wasn’t going to do the “sounds like” thing but indulge me once: this is Kanye’s attempt at the Phil Spector-like wall of sound:

Sound and Statement and Messages and Mediums

The sample in “Home” wasn’t just a fun background. Just as Mr. Redding’s voice will boom throughout the exuberant “Otis,” Kanye is instructing and building with the past. In a recent article, I talk about how Kanye used samples of Gil Scott Heron to weave a dialogue across varied albums to display transmedia practices.

What I want to point to here is that these are confrontational samples. When I think of “Home,” it’s not of the run-of-the-mill lyrics. It’s Labelle’s voice over and over, phasing in and out like a modernist classical composition. It’s minimalist with little more than the start-stop skittering beat to propel the song forward. This is a foundation.

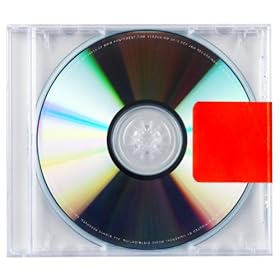

Kanye’s work has been orbiting this constellation of minimalism even when his own rants seem endless. [Aside: No one does the rant better than Kanye, “But my greatest pain in life is that I will never be able to see myself perform live.”] From the largely rap-less 808s and Heartbreak to the piano+shouting loop=hit song of “Runaway” to the nothing-there, iconic cover of Yeezus, Kanye’s work can be understood as using less to confront and challenge. Lyrically his is work that is outspoken and problematic.

And the medium in pop culture is the tweet-able outburst. Kanye is so public in our eyes because he is saying things that makes a white hegemony shake its head. His confidence extends beyond what is acceptable within the niche market of hip-hop. When Kanye says “I am a God,” we squirm. [Aside: English teachers might want to use the song’s title to differentiate between metaphors and similes.]

The non-commercial qualities of Kanye’s latest album, Yeezus, to me, seem to push directly against what consumers count as hip-hop today. In the same quarter that Jay-Z attempted to appropriate the Magna Carta, Nirvana Lyrics, and Marina Abramovic’s work, in an attempt to capture sales, Kanye’s lead single was a minimalist song with little beat and lyrics that are all but unplayable on the radio. For fans anticipating Yeezus the rest of the album followed the same musical and lyrical motif as “Black Skinhead.”

Which brings us to “Bound 2.”

Bound for Glory

On November 25 (the day before my Pirate Ship tirade), I retweeted the following:

#snap RT @noyokono: So is Kanye allowed to do anything without white people making fun of of it?

— anterobot (@anterobot) November 25, 2013

The context was a shot-for-shot remake of a tawdry video Kanye made for his song “Bound 2.” The remake was funny. I get it. And I can see why Kanye’s video isn’t very good (though I do suspect he is making a move at having a seat at the pop-art table along side the work of Ed Ruscha, Damien Hirst, and Andy Warhol). I can see a gallery aesthetic here that ultimately failed and opened him up for parody.

But what is “Bound 2?” With hyper-masculine lyrics I won’t excuse here, Kanye is defining swagger and challenging rap music. Bound 2 says, Oh, you like those sped up soul samples? Well, here you go. Deal with THIS. The same wall of sound of “Home” is present here. Kanye is throwing his musical thesis in your face – take it or leave it.

Uh Huh Honey

And it is this confrontation that matters. We’re 2,000 words in here and this is what I need to tell you: when Kanye makes you uncomfortable–be it through his unapologetic beats, his uncomfortable lyrics, his troubling iconography, his in-the-news-black-man-out-of-control rants–he is attempting to rewrite the role of the marginalized. He is forcing us to see Kanye and acknowledge him.

What’s more, we need youth today to see men being seen like Kanye. When Kanye says he is a god or he wishes he could see himself perform or that he wants to reinvent high fashion, he is affirming his existence in ways that youth today need. More than ever. Reading the biographies of tech legends over the summer–Steve Jobs and Jeff Bezos–you know what they had in common? They were uncompromising jerks. They would throw fits to get their ways. To get people to “think different.” And we laud their efforts today.

When I taught 11th grade English, an instructional unit that I really appreciated developing over the years was one that paired the canonical text, Shelley’s Frankenstein, with research on graffiti in Los Angeles and the documentary film Bus 174. The unit asked my students to look at how social monstrosity is constructed. We looked at how a bus highjacker in Brazil confronts society and moves from being invisible to a violent “threat.” I am reminded of this unit as I attempt to wrap up this length rant.

In recent months, Kanye has redoubled his efforts to confront Western society with his brash and outspoken behavior. He is reaching out and rejecting the labels we cast on him.

I’d made a list of the things Kanye had disregarded over the course of his developing career but realized is was neither comprehensive nor necessary for an already rambling post. Instead, I want to pose that Kanye is the race-conscious rapper that the DVR and Snapchat generation needs (now that I know what Snapchat is). In an era when texts and pictures can be sent and viewed before disappearing into the ether, Kanye presents us with sounds and images and ideas and beliefs that don’t disappear. He is a visible man that affirms that he–like Ali–is the greatest. His unyielding belief in himself a beacon of confidence for his youthful listeners.