My current research on tabletop roleplaying games can be understood as part of a larger movement by researchers. In particular I have been considering the ways individuals interact, learn, and communicate in virtual worlds. Because the virtual world interactions I’ve been observing in tabletop roleplaying games seem to differ from those in online environments, I wanted to sketch out my general understanding of immersion within these spaces.

Defining Virtual Worlds

In their book Ethnography and Virtual Worlds, Boellstorff, Nardi, Pearce, & Taylor identify four characteristics that help define “virtual worlds” (page 9):

- They are “object-rich” environments with “a sense of worldness.”

- They are “shared social environments.” Participants can interact with others within these worlds in real time.

- These worlds persist over time. Though a participant may disconnect from a virtual world, the world may change or grow over time. [I’d note here that while time proceeds within virtual worlds it does not necessarily do so at the same rate as that of the ticking clocks of the “real” world. During a major showdown in Eve Online, for example, the game moved at one-tenth the speed of normal time to help ensure players’ actions were processed correctly. Likewise, in future posts I will discuss the ways time unfolds in tabletop roleplaying games.]

- Virtual worlds provide participants with the opportunity to “embody themselves.” Using avatars, participants can move about and explore the world.

Examples of virtual worlds within this definition include the World of Warcraft and Second Life (both of which have been explored in foundational virtual worlds ethnographies by two of the authors mentioned above). The authors specify that online social networks like Facebook and digital discussion forums are not examples of virtual worlds. They claim that, for instance, these spaces do not include the “worldness” or “embodiment” that is integral to virtual worlds. This is an argument I’m not entirely convinced I agree with. As I watch my wife’s fingers help her meander her way across the updates and statuses of “friends” on her phone’s Facebook app, I see an immersion and embodied, representative sense of self that is patently different and representative of her own identity. My own ethnographic travelings within and around tabletop roleplaying games and virtual worlds has sometimes focused on blogs, discussion groups, podcasts, and uses of online social networks. I will be discussing how these may or may not extend our understanding of social networks as virtual worlds later on.

On Immersion in Virtual Worlds

Let’s start with the literal to talk about the virtual.

Immersion can be defined literally (according to my dictionary) as placing something fully within a body of liquid or as delving deeply into an intellectual subject.

As if subsuming one’s body within a pool, we immerse in virtual worlds fully. At least that’s what is suggested by the metaphor of immersion in virtual worlds. The standard narratives are of people who get lost in the virtual worlds of The Sims or WoW. There are the stories of some poor schlubs who die from being overly immersed in the virtual.

However, in tabletop games that’s not really the case.

On Snorkeling

During my honeymoon in Belize recently, I was talked into (possibly coerced into) going snorkeling on the lip of the Belize Barrier Reef. This would not have been a problem if I knew how to swim but alas that is not the case. I am something akin to a lead pipe in water and the process of jumping into a large body of water (even with two life preservers) was one of the most terrifying experiences I’ve had. And yet, after finally calming down and beginning to explore the wondrous world beneath me, I was thrown by the beauty of the ocean. I would take small visual sips of the world, placing my head down and allowing the oceanic world to enter my vision before assessing my general position to the boat by coming back up into the real world. Gradually these sips became longer and longer as I allowed myself to trust the plastic snorkel’s function and remain in the underwater world of the reef and coral and fish. However, I would, eventually, have to return to the world above water from time to time.

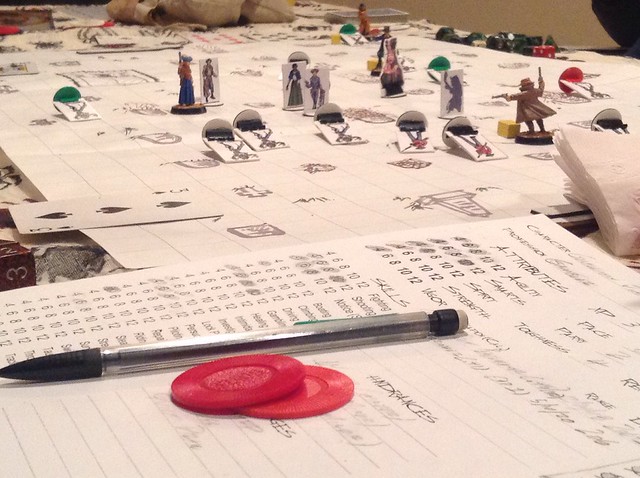

And this is a lot like what virtual worlds are like in tabletop roleplaying games. The idea of being trapped for hours in the time-sucking world of a game like World of Warcraft doesn’t function the same in tabletop roleplaying games. Interactions with other players dips participants in and out of the virtual world. Part of the process of playing a roleplaying game is the table talk with other participants: catching up, joking, talking about movies or other games; camaraderie is developed through the more-than-just-roleplaying aspects of time at the table.

Further, game mechanics require us to step away from immersion. We take sips in dialogue and engagement within the virtual worlds we explore but return to the physical world to check rules in books, roll dice, and refill beverages. We can imagine our interactions in the fantastical worlds of Numenera or Golarion as the equivalent of snorkeling. As we look down into the hand drawn maps and scattered dice below and in front of us at the gaming table, we cannot fear getting too lost here: we come up for air regularly and return to the physical world.